Thoughts, quantitatively powered.

Lifehack: get up earlier, not-a-morning-person; VCs are not parasites; the power of love… of numbers; and some culchur.

Not a morning person? Get up earlier!

I’m not a morning person. Technically, I’m a late chronotype, someone whose energy level rises slowly after waking up, peaking later in the day that most people. There are about 10% of us, and about 5% of the opposite, people who jump out of bed full of energy.

The usual recommendations for late chronotypes (or for dealing with them) are to sleep late or to move work to later in the day. The first recommendation is counterproductive, as we’ll see below; the second shortens the workday for people working in teams.

And teams, or work involving others, is really the issue: if one is working alone, it doesn’t really matter whether it takes two hours or fifteen minutes to start work, as long as the total day energy ends up being the same; but is one has to coordinate with others, that’s were the problems start.

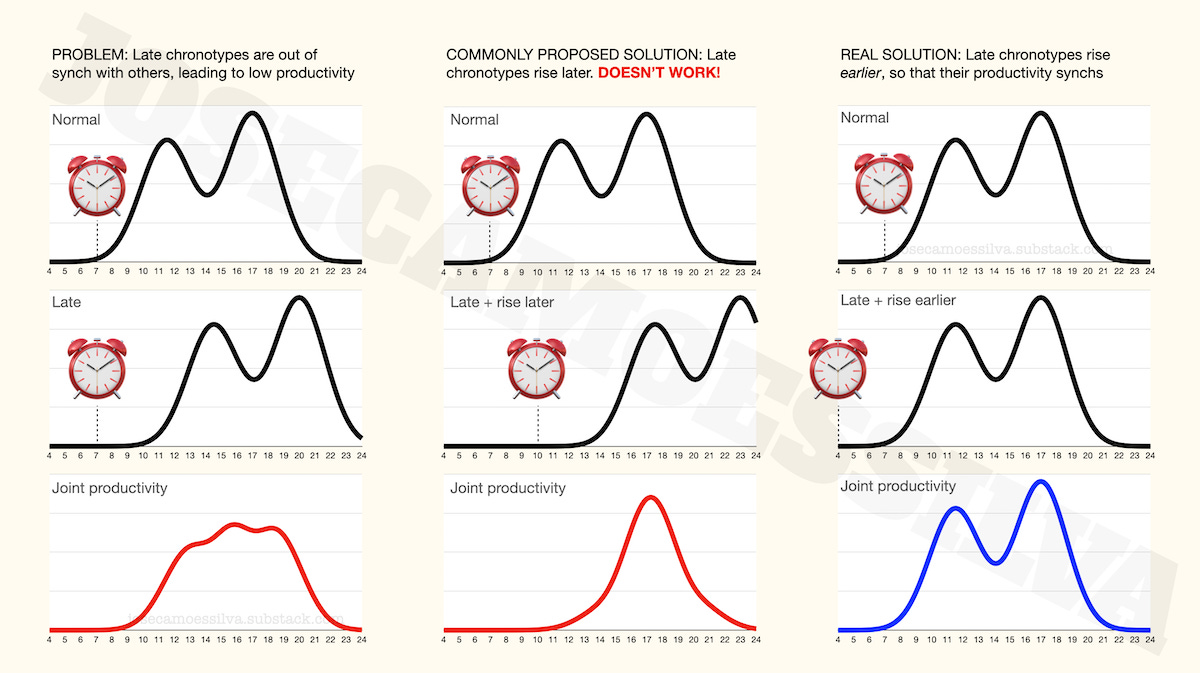

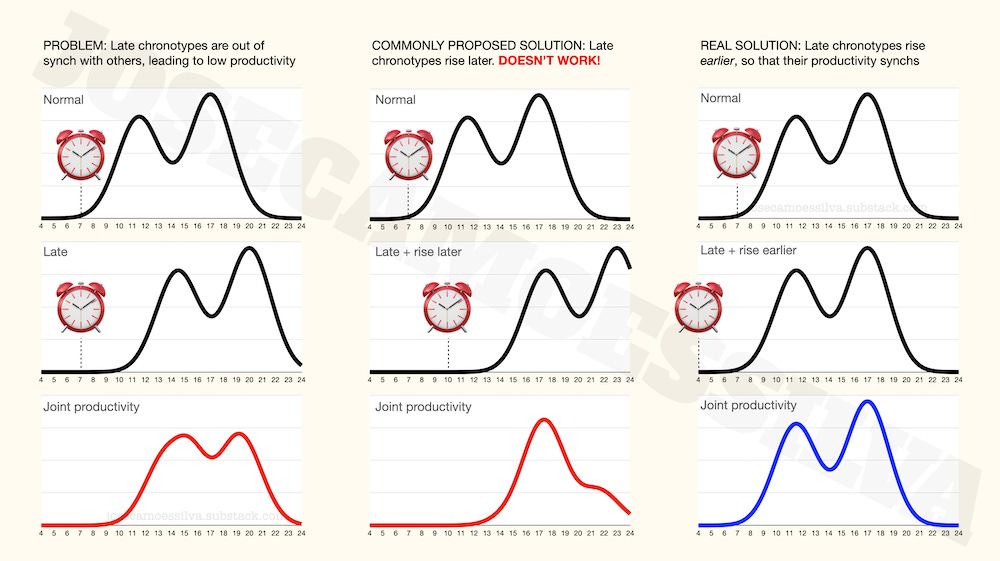

To illustrate, let us build a toy model, where there are two peaks in personal energy (to account for a post-lunch dip), everyone has the same energy trajectory though it may start later after wake-up, and the joint production function is non-linear but homothetic (so that working together is much better than separately, but increasing resources proportionally just gives a proportional response).

Using this toy model, and assuming both types contribute equally to the result, we can compare the base case, the “get up later” recommendation, and the alternative, getting up earlier:

If we allow the late chronotype to be the more important part of the production function (which modesty forbids to assert as an outright statement, but allows the assumption for discussion purposes only), the value of getting up earlier is even more obvious:

No, VCs aren’t parasites on the creativity of others.

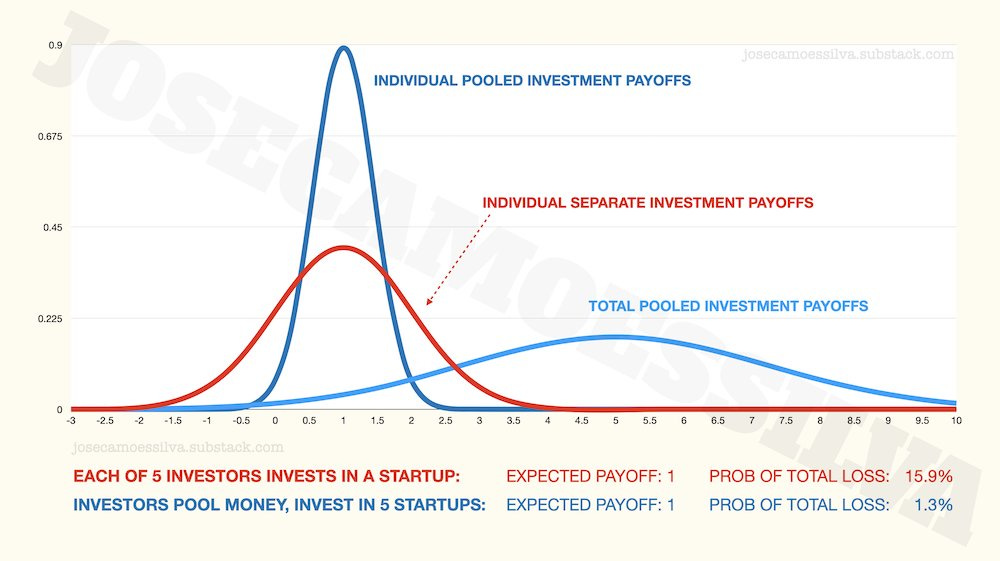

First, they prospect and pool liquidity to allow investors to bet on portfolios rather than individual startups; this reduces risk. (Yep, finance 101; but I keep having to explain it to people.)

For example, let’s say there are five investors and five startups, each requiring an investment of 0.25 [million spondulix] with an expected payoff of 1 [million spondulix], normally distributed with SD=1. If there are no intermediaries in the economy, and each investor pairs up with a startup, each of them has an expected undiscounted return of 300%, but with a 16% probability of total loss.

If a financial intermediary gets the investors to pool their money and to use that pool to invest in all five startups, their return is still 300% (minus the cost of the intermediary) but now the probability of total loss is only 1.3%.

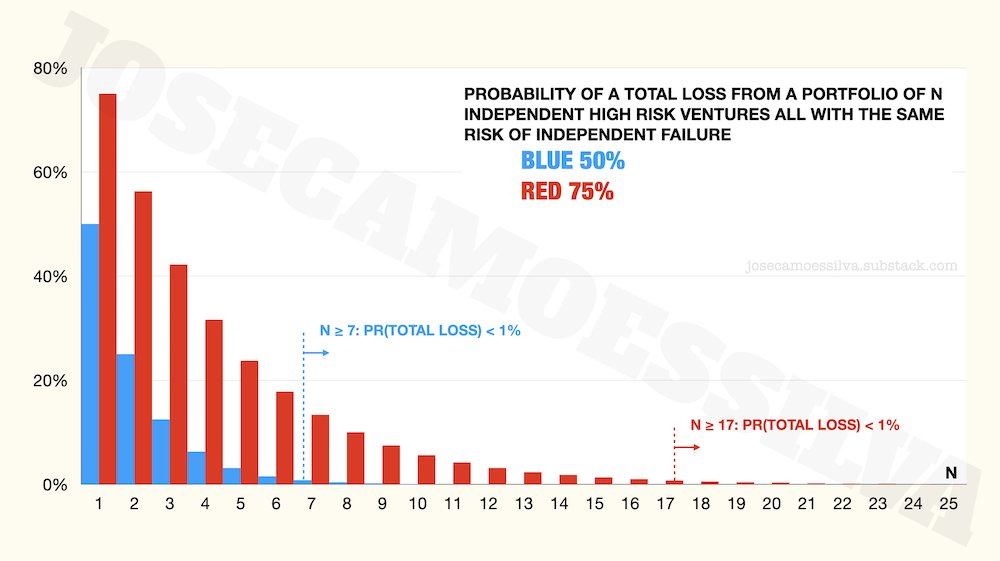

The importance of portfolios becomes even greater with high-risk ventures (which many startups are). For example,

And that brings us to the second service VCs do (as financial intermediaries; since Kleiner-Perkins appeared and changed the rules they also act as management consultants and network facilitators): the selection of investments.

Consider a rich but not knowledgeable investor, Filbert; he might be able to finance a portfolio of startups, but without the ability to select them (or provide consulting and networking), the startups in his portfolio will have a higher risk of failure (the red ones in the chart above).

Conversely, VC Jacqueline can select and advise companies therefore reducing the risk; because these are startups, there’s still a lot of risk, but if her services bring down the risk of total loss to 50% in each startup (assumed independent, though VC firms tend to specialize, so there would be some element of correlated risk), that’s a valuable service as seen by comparing the blue and red distributions in the chart above.

Of course, some of their number are a little oblivious to their public image so they provide a never-ending stream of entertainment, curated for example by the twitter account VCBrags:

The power of love… of numbers.

With apologies to Frankie Goes to Hollywood and Gene Hackman in The Heist (2000).

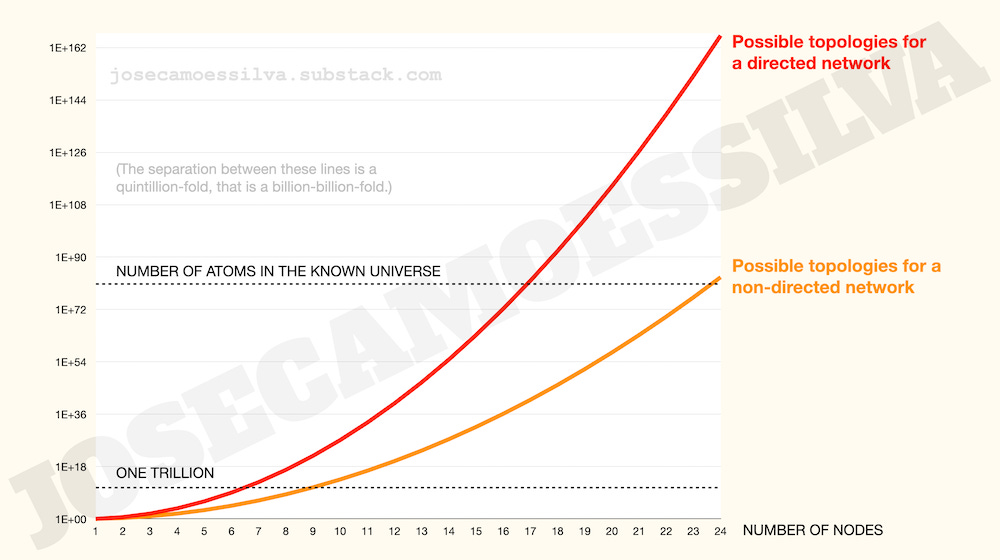

In a recent post we saw that network topologies (different ways to connect the nodes in the network) grew very fast. How fast? For a directed network (like Twitter — rebranding be damned), all it takes is 17 nodes for the number of possible networks to be larger than the number of atoms in the Universe:

Such is the power of numbers: a little investment in treating them as information (as opposed to props, which is how much of the discourse around numbers treats them) pays back in deep insights, such as “don’t try to analyze network in detail, use statistical methods to understand underlying structures.”

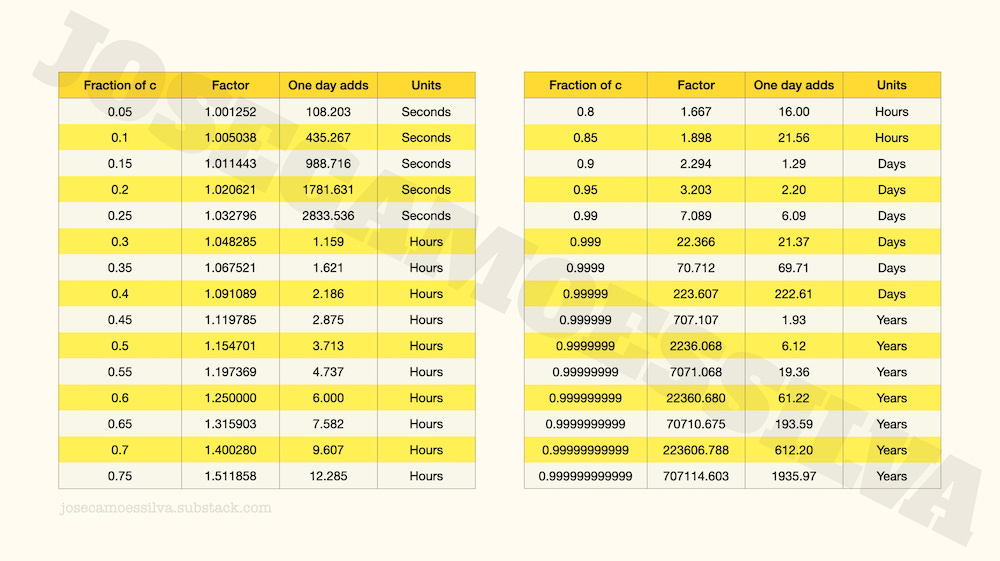

Another example, sadly a common problem in otherwise good “hard science fiction,” overuse of Special Relativity to create time travel.

Typically there’ll be some ship going a percent of the speed of light (say 5%) and the effect is to pass time very fast on the fixed reference frame. So the ship The Conglomerate under command of Captain Jeanne Pickering leaves Earth at 5% of the speed of light and comes back the next day (ship’s clock) to find Millennia have passed.

The problem is that at 5% of the speed of light time dilation is minimal: Earth would have only gone less than 2 minutes into the future. In fact, to get anywhere close to a noticeable time dilation, The Conglomerate would have to be going very very very close to the speed of light:

Of course, there’s always warp speed… oh, wait!

Technology, redux.

Original screenshot: NCIS Sydney.

De gustibus non est disputandum

(Arts and entertainment corner. Personal opinions; see heading.)

Books. Courtesy of Standard eBooks I’ve been rereading some old classics (free!), including

All quiet on the Western front, by Erich Maria Remarque;

The Man of Destiny, by George Bernard Shaw; and

The Secret of Chimneys, by Agatha Christie (neither Poirot nor Miss Marple).

Food. For persons of size who get called on it, Mr. Maximillian Vandeveer has a riposte:

From “Who Is Killing the Great Chefs of Europe?”

More food. Bodybuilder Valdislava Galagan tries coffee in Vietnam:

Music. In jest I referred to technical analysis as having rules like “when the 5-day moving average crosses the 30-day moving average from below, the Moon is in the seventh house, and Jupiter aligns with Mars, sell.” Asking Grok for an explanation, it missed this classic piece of Americana:

Grok’s take:

As for Tesla’s performance year-to-date, what’s a 38% drop in 2 1/2 months among cult members?